Profiles in Light: Bret Curry

Cinematographer. Photographer. Creative.

One of our favorite visual artists, Bret Curry is a man whose many talents are uncommon to find wrapped into one individual. But the word “talent” often cheapens a life of hard work. Perhaps the greatest accolade, often unintentional, that can be given to a master of his art is for it to seem only natural - to make it look easy. But we do well to look beyond the final exposition: to focus in on the details and study them closely, and in those details the true life of the work becomes evident, along with that of the person who created it.

Bret’s work is unusual in its scope. As a Director of Photography (DP) on movie sets, he’s the man who makes a director’s vision come to life - the lights, camera, and setting of the shots that bring characters off a screen and into your head and heart. As a photographer, he works in a different medium: however many technical similarities “pictures” and “moving pictures” contain, the approach, and the results, are wholly different and distinct unto themselves.

Few noted photographers work in cinema. Few cinematographers are noted photographers.

In Curry, we find both, along with other elements of a life well lived, as we’re fond of showcasing here. So without further ado, we’re pleased to share with you our latest edition of our Profiles in Light series - after which we hope you’re inspired to pick up a camera and disappear down a wide expanse of open road.

You're a photographer and cinematographer. What drew you to visual arts?

When I was a teenager in the early 2000s a few factors combined to set me on this path. The confluence of skateboarding culture and access to peer-to-peer file sharing provided the spark and the fuel. The intro section to one skate video in particular, Transworld’s Anthology, was incredibly important to me at that time. That montage underscored by Sebadoh’s “Skull” is something I watched hundreds of times. I began to try to reverse engineer what appealed to me about the combination of certain visuals and sounds - figuring out what camera equipment and what software I needed. That is still the core of my work, both with stills and motion – solving technical problems based on some initial thesis, idea or set of influences. It’s also a similar process to skateboarding – looking at a concrete set of factors and trying to find a creative solution to getting past them – and attempting to hide that process so the viewer just sees the art. Although seeing the process is also very interesting – which is why I love looking at behind-the-scenes footage and photos from art that I love.

Is there anything in particular that informs your approach to a scene? James Stacey mentioned that your photographs feel like a memory of a moment - maybe better than it was, but still with a feeling like your own eyes saw it.

That is a very kind and insightful observation by my friend James. Like I stated above, you are always dealing with some immutable facts about the landscape that you approach, but you begin to recognize patterns more quickly the more experience you obtain. There are many factors you can’t control – but there are countless interesting ways to combine those elements in ways that you can. You start to develop an intuition for what feels right – and little fallback rules for when you’re stuck or need to force the process along more quickly. There is a universal truth to things like “the rule-of-thirds”, “vanishing points”, “color theory”, etc. These are all ideas you can study in books or on the internet, but you probably already understand them well from ingesting so much visual media throughout your life. Ultimately, I want to create something that stands on its own and I tend to lean into traditions or some sense of universality to do that – but also produce something that conveys a slightly heightened reality – which is very similar to the experience of memory.

You've traveled across the United States pretty extensively by car. What has struck you most along the way?

First off, the sheer variety of natural beauty in this country is staggering – as well as the amount of land that is still uninhabited and the vast distances between civilization (save a gas station) in many regions of the western states. I’m incredibly grateful for the modern comforts of road travel and for the incredible road infrastructure built in the past century. I would always prefer the freedom of traveling by car to the expediency of air travel. The fact that I even have the assumption of that choice as a common person is proof we live in an incredibly privileged time.

What has struck me the most is how similar all the cities are now and the lack of a sense of regionality and place when you are within them. A lot of character has been forfeited to convenience. A lot of small business and community sacrificed for countless unsavory reasons. In relation to cross country road travel, large cities have been reduced to reliable pit-stops and outposts but they are rarely the destination. Towns with smaller populations and old “blue highways” are by far the most interesting – especially visually – but they are also not a destination. I feel like I spend most of my life in transit and not settling in or relaxing in any spot. I don’t even feel settled in in the city or home I live in – it feels like a pit stop to the next location.

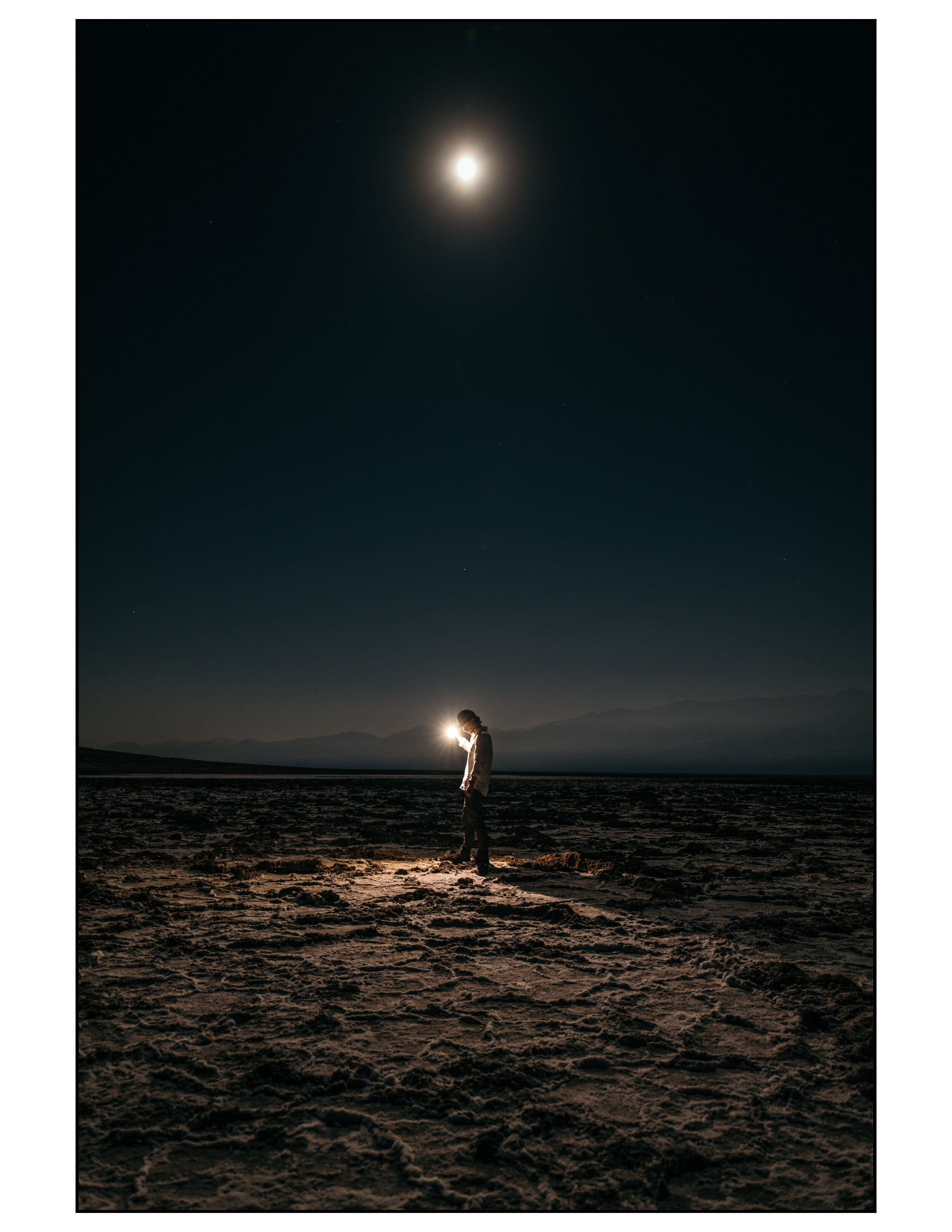

It seems you spend a decent amount of time in the dark with some of your photography. What's your favorite place to spend a night beneath a dark sky?

Night landscape photography is actually something that doesn’t hold much appeal to me other than as an interesting problem to solve – that problem being the difficulty in differentiating your images from anyone who knows the techniques to pulling them off. It’s an uncommonly technique driven subgenre of photography and thus people tend to overcomplicate an already complicated process. That being said – the experience of shooting in a truly dark environment where you can locate the Milky Way visually without aid of an app is great fun. Living in Los Angeles, Joshua Tree is by far my favorite place for this. You always know where you are, there are safe pullouts and campgrounds, and the trees and rock formations provide tons of compositional options. National parks and forests are the ideal spot for messing around with this technique but more than anything it’s just a great excuse for a unique experience. Recently I was at Badwater Basin in Death Valley at 2AM with nobody else around. I can’t imagine a closer experience to being alone on another planet.

Film vs. Digital: What drives your choice of medium when you're working on a project?

This answer will apply to both stills and motion – but professionally in this modern era, always digital unless the client or director expresses an extremely strong desire for film and understands the limitations involved. I often supplement with film on projects but rarely is it requested as the main capture medium – there are too many conveniences associated with both the on-set monitoring and post-manipulation to justify shooting on film for 99% of projects. I did not come up in an era where shooting film was the only option, but I was just on the edge of it – the RED ONE, Arri Alexa Classic and Canon 5D II were the cameras of my post-college career. Film occupies a strange place among current DPs and photographers (particularly of my generation) as a tool to try to engineer some sense of old-time competency in an era when all our peers are highly digitally literate. There are viable aesthetic reasons, although too often an it’s an aesthetic of fetishized sloppiness. Unfortunately, shooting film seems to be beyond the technical competency of many of the people who lean on it the most – but there are many people who still do incredible work with it.

That being said – the process of shooting film and the direct and indirect lessons to be learned from it are extremely worthwhile – and there is a quality to the images that I believe comes from a few factors. One is the reliance on stricter and slower standards and practices to achieve a well-exposed image. Two is the now centuries of work and experience that have gone into creating these film stocks and the supporting chemistry and tools. I am very glad to see such a resurgence of interest in film photography, even if it turns out to be a temporary fad, as at least a last hurrah of one of the most important tools of the 20th century.

What's your favorite film emulsion, and why?

For motion stocks, any current Kodak Vision 3 stocks are essentially the only options.

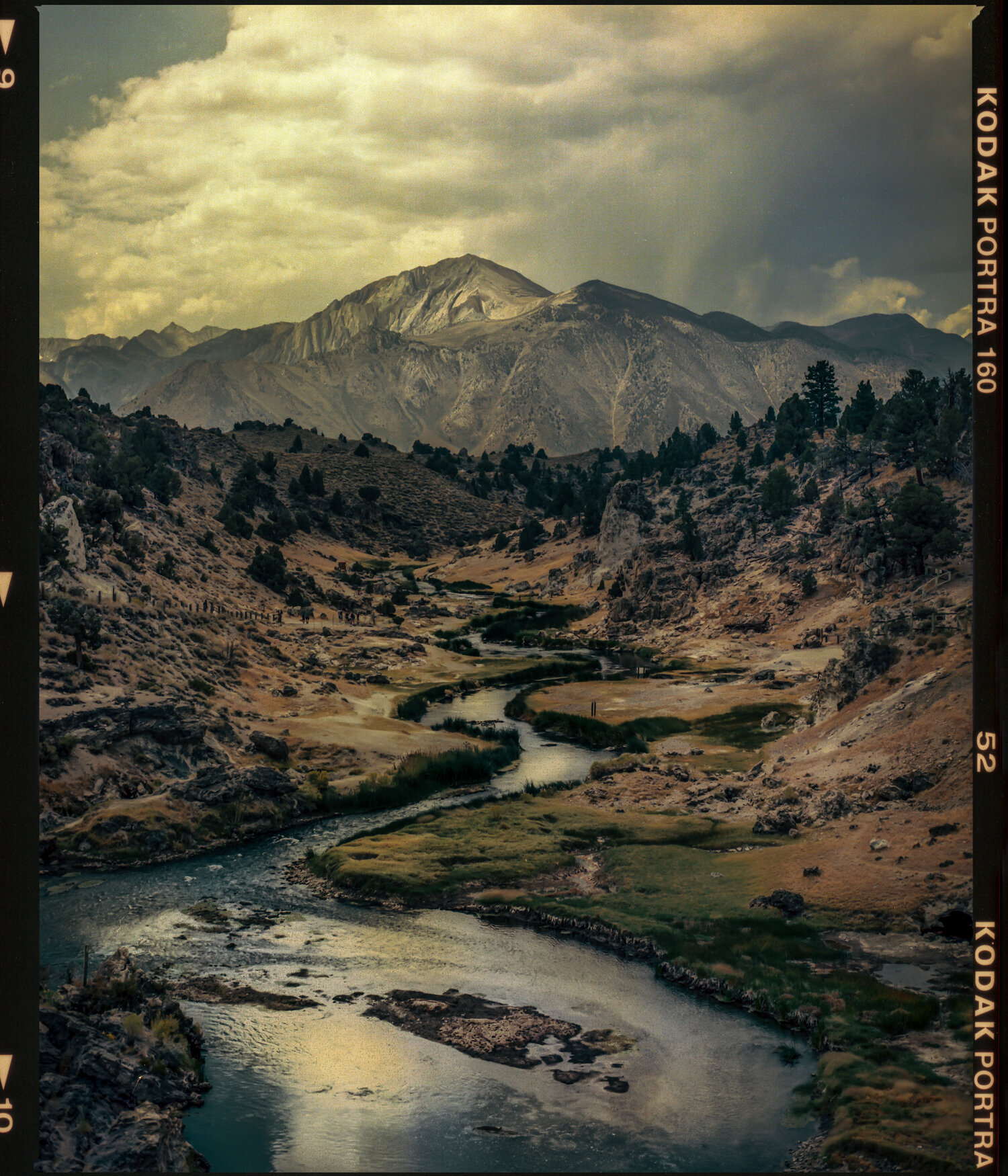

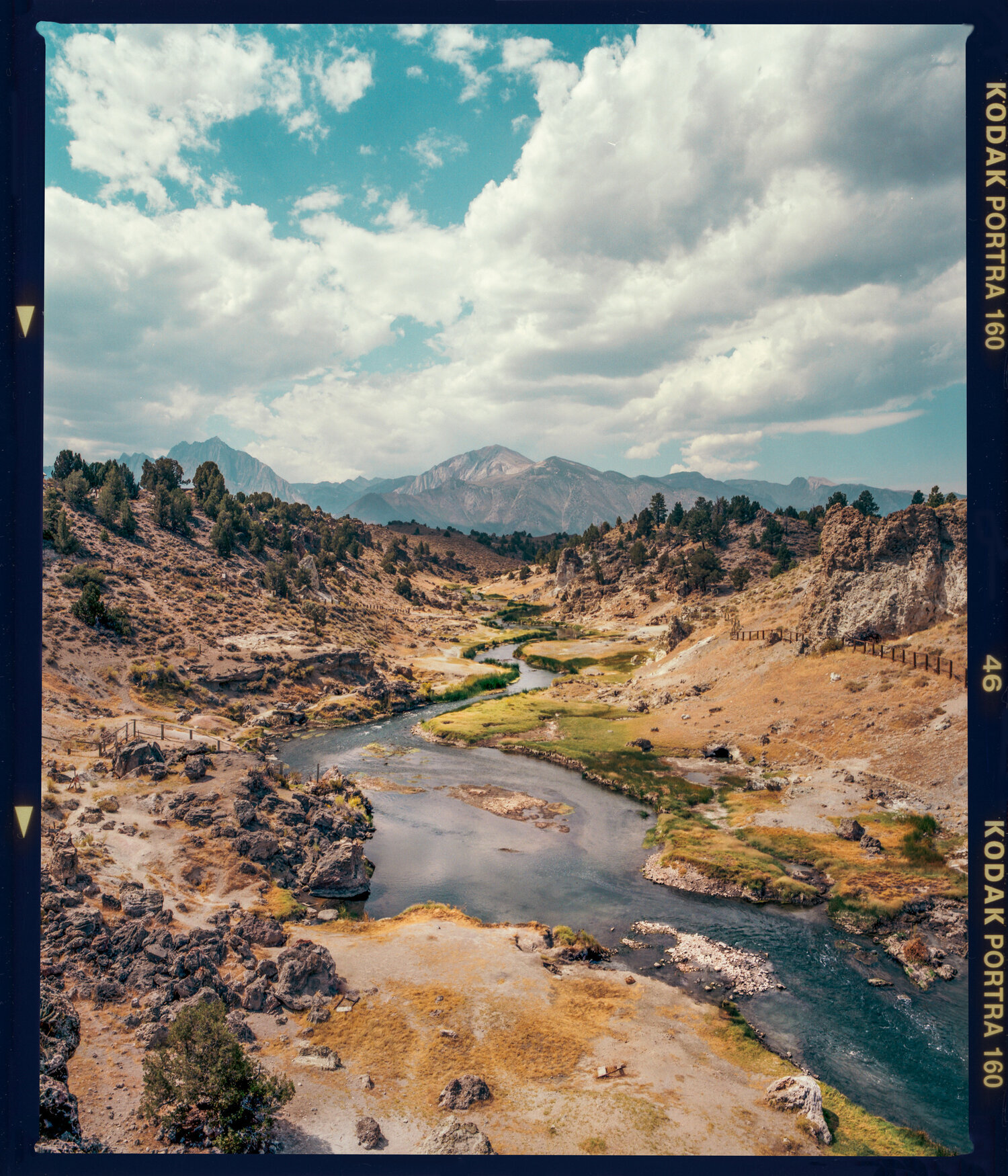

For stills, I prefer Kodak Portra 160 and Ilford Delta 100 in 120 format shot at box speed. From those choices you can guess that I’m not a big fan of grain in still images. Portra 160 renders beautiful skin tones and neutral colors and Delta 100 has a beautiful combination of sharpness, contrast and smoothness that I think is the most pleasing of any black and white stocks.

Do you have a favorite set of equipment, or at least one that you find yourself gravitating towards most regularly?

For motion my favorite camera to work with is the Arri Alexa. In terms of motion lenses – I love the Leitz Summilux and Summicron sets for Super 35, the Arri Signatures for full frame and Panavision T and C series for anamorphic.

On the stills side, the two cameras I use the most are the Leica Q and the Mamiya RZ67 Pro II. They are good complements to each other – both scratch different itches in terms of physical use and post-process but the imagery achieved from them both intercut well within a project or feed.

I picked up the Leica Q about a month after it came out in late 2015 and have been using the same camera ever since. I truly think it’s in the top 5 cameras ever manufactured – it is just an incredible combination of elements. To describe it as a Leica M with all the modern conveniences and a 28mm that is sharp at 1.7 says it all. For a camera that essentially functions as an advanced point-and-shoot the image quality is incredible. I have not upgraded to the Q2 yet, but they recognized what a great job they did with the first version and just made the right iterative improvements.

I’ve rented and borrowed the Mamiya RZ67 Pro II for years but finally picked up my own a year or so ago. I love the 6x7 format and the lenses for that system are just incredible, particularly for the prices you can get them for now. I have a hard time getting motivated to shoot 35mm stills but I think medium format still has a viable place professionally in 2020. There is still a quality to price ratio that you can’t match digitally – and the experience of using a big, bright waist level finder like that on the RZ67 can’t be beat.

Can you tell me a bit about your work in cinema?

From around age 16 I began making short films with friends in Dallas/Fort Worth and from there I graduated with a degree in film from the University of Texas at Arlington. During those years I met a number of Texas filmmakers who I continue to work with and an internship with Getty Images that set me down the documentary path that I work often in today. I spent about 6 years post-college working on independent features and shorts, various commercials and music videos, and a series of documentaries in remote regions of India, Mexico, and Alaska. In 2016 and 2017 I shot a few series for National Geographic and also was fortunate to work that year on David Lowery’s film A Ghost Story, where I acted as Gaffer, 2nd Unit DP and Stills. Many of those behind-the-scenes stills have become fairly well-known and circulated. My wife and I moved to Los Angeles in 2017 and I’ve been primarily shooting documentary series for the past few years, including AMC’s History of Horror for director Eli Roth and the AppleTV+ Visible for director Ryan White. During that time various narrative projects have been in development – which is the area of work I plan to emphasize much more in the next few years – as well as expanding my stills work.

For those less familiar, what's the usual role of a DP on set?

There are two essential roles for a DP – the first is to interpret and facilitate the visual capturing of a director/clients vision and by extension the second is the management of the camera and lighting departments on set. The process begins with discussing a script or concept with a director or producer that has come to you based on a previous working relationship or previous work that they have seen of yours. From there you will get an idea of their desires and their visual taste and start to get a rough idea of how you will approach things given the working budget. This is where the true pre-production phase begins – where you start to make crew, equipment, shotlists/storyboard and scheduling decisions. Your relationship with production design, art and wardrobe is of equal importance beginning in pre-production – because you can have the greatest camera equipment in the world but it won’t matter if what is on camera isn’t serving the project and it’s visual needs. Also you will speak to any post-production and VFX people at this time to ensure that they are getting the raw material they need to do their jobs. On set – you will continue to coordinate alongside the director and other crew heads and most directly with the camera and lighting/grip team to direct the camera placement/movement, lens, lighting and grip needs. I operate on most of the projects I am involved with, but the camera team will include other operators, 1st and 2nd assistant cameramen, and a DIT (Digital Intermediate Technician), which most often is applying onset grades, additional quality control and backup of media. In post-production, your role is to advise as needed during editorial and to supervise the color grade when it gets to that point. It’s quite a process but one that has been standardized over a long period of time and allows room for (some) creative expression in the midst of all the button pushing and knob twisting.

Cinema and stills are very different mediums for story telling even though the basic premise of the two is similar. A good photograph can capture attention for a long time within a single frame and is something of a solitary experience. Cinema is a completely different experience altogether. How do you convey the emotion or intent behind a scene in each medium?

Very well put. One medium allows your eye to wander freely and the other directs it – but it isn’t quite that cut and dry. Among other examples, you think to Kubrick, a photographer turned director and whose approach is an obvious blend of the benefits of both mediums. To a great extent, Terrence Malick and Emmanuel Lubezki do the same thing, but much more handheld, with wider lenses and less static intent. My favorite balance of the two is someone like Roger Deakins, who is all about composition, rarely shoots long lens or over-covers a scene. His work feels less obviously inspired by the stills world, but it is the perfect balance of allowing breathing room and context while still directing the viewers eye. Usually the script/concept, performances, blocking and location inform the visual approach to conveying a particular feel or emotion – and many times you don’t know until you get the camera in front of you. That is why it is important to have a plan but always be flexible enough to change it if a better way reveals itself – and it usually does.

What's your dream project? Budget filled, production team of your choosing, what story would you want to tell?

My absolute dream project isn’t anything in particular – if anything I’d love to continue working for as long as I am able to in as many different genres and worlds as possible – either through motion or stills. You always hope for more resources and more support – but there is always a balance to budget and control. It feels like the middle of the industry has fallen out and I would hope for a return to some form of balance in the future – where there are more projects that have a balance of resources. It’s exciting to see people work at the upper echelons of production and aspire to that. I think to four films that were released in 2007 – No Country for Old Men, Michael Clayton, There Will Be Blood and Atonement. That is the exact level of production that I aspire to – that sort of balance. I’d also love to work on a series like Mad Men, to have to sort of involvement that DP/Director Christopher Manley did. 2007 was a big year for this stuff.

Road Trip. Choose your car, destination, and route. Who and what do you take with you?

My wife and I travel multiple times per year by road between Los Angeles and Texas – so we know the southwest and all the good pit stops between there almost too well. And I’ve been all over the US by car for work, so as much as I love it, I’ve seen a lot of it.

I’d say a few week long road trip around the Alps in something comfortable! A Volvo V90 Cross Country would do – or an Audi RS6 Avant. That sounds really nice.

A big thanks to Bret for taking the time to share insights into his life and process with us, along with the collection of beautiful photographs featured in this article.

You can see more of Bret’s work on his website and on Instagram.

When roaming around the world, Bret can usually be found in his VW Golf GTI, with a Tudor North Flag on his wrist, and a Beagle Electric Torch in his pocket.

Bret Curry exploring Death Valley National Park with his Beagle Electric Torch